A

Yang for Every Yin |

|

Dramatizations

of Korean Classics |

| |

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

| John

Holstein. (2021). A Yang for Every Yin: Dramatizations of Korean Classics.

ISBN 978-89-285-1608-7. 351 pages. A CD is included. |

| |

| With this

book the general reader gains access to a few of Korea’s favorite

classics. These plays are based on stories from Korea in the 17th and 18th

centuries, and they are still being told in the twenty-first century, in

their original form but also on TV, stage and film. Four of the five plays

in this book are dramatizations of pansori, one of old Korea’s most

highly-developed performance arts. (You may already have heard about Chun

Hyang, Hungbu and his brother Nolbu, Hare and Tortoise and the Dragon King,

or Ong Go-jip.) The other play is based on the popular traditional short

story, Grandpa’s Wen. |

| |

| |

| |

|

| |

| Synopsis

of each play |

| |

| Harelip |

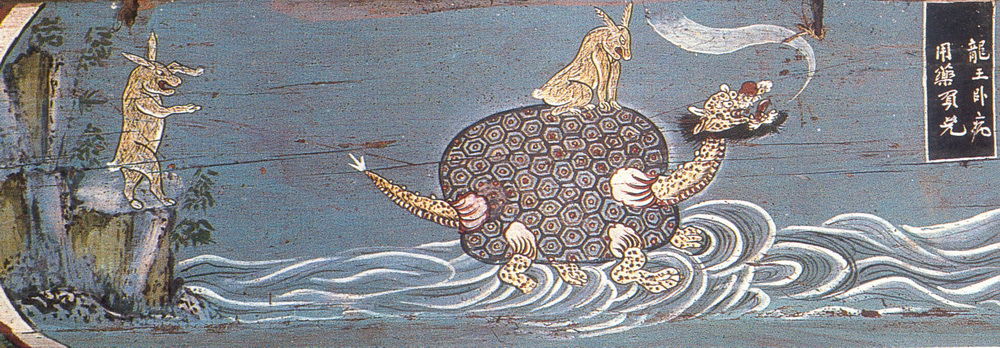

| In

the Palace of the East Sea the ten-thousand-year-old Dragon King is dying

from a disease which can be cured only with the liver of a hare. The King’s

faithful thousand-year-old Chief Minister Tortoise makes the difficult

and dangerous journey to land, where he succeeds (by playing on Hare’s

vanity) in luring her to the Sea Kingdom. When Hare discovers they want

her liver she claims that she took it out that morning and hid it away

for safekeeping. Tortoise reluctantly brings her back to land to get the

liver, but Hare escapes and then, mischievously adding salt to Tortoise’s

wound, gets him to accept three of her foul-smelling “instant concentrated

rabbit liver tablets” as a substitute for her liver. She bounces

off into the forest laughing, leaving Tortoise to return to the Dragon

King empty-handed. But hers is not the last laugh. |

| |

| |

| Grandpa

Lopside, a poor woodcutter with a wen on his right cheek, is caught in the

mountains by a cloudburst one day and forced to spend the night in a deserted

shack frequented by goblins. Just as the goblins are approaching the shack

Grandpa launches into a song to ward off the uneasiness he feels at being

alone in the spooky woods at night. The goblins, who love good singing but

are notoriously bad singers, burst in on him and demand more. At the end

of Grandpa’s song they offer him a sack of gold for the “song

bag” on his cheek. He insists it’s not a song bag; but they

think he’s just trying to keep it for himself. So they snatch it from

him and leave him the sack of gold. Within a few days Grandpa’s wen-bedecked

friend “Grandma” Lopside (as tone-deaf as the goblins) hears

that Grandpa has become rich, and in his greed schemes not only to get rid

of his wen but also to get some gold. He goes back out to the shack and

tries to deceive the goblins. Meanwhile the goblins have discovered that

Grandpa’s wen is not really a song bag. So Grandma Lopside, instead

of getting rid of his wen, ends up with Grandpa’s wen on his other

cheek. But this is not all he gets. |

| |

| Two Kins’

Pumpkins |

| Wealthy

Father has died, and first son Nolbu has control of the entire inheritance.

This mean and greedy Nolbu can’t stand the idea of sharing the inheritance

with his virtuous younger brother Hungbu. So he kicks Hungbu and Hungbu’s

whole family out of the house. They barely survive a year of hand-to-mouth

existence. Then a swallow, whose broken leg Hungbu has fixed, returns the

next spring with a reward of magic pumpkin seeds, and when Hungbu harvests

them in the autumn they yield a cornucopia which makes Hungbu even richer

than Nolbu. Nolbu and his wife hear about this and hunt down a swallow,

then break its leg and fix it so they can reap the same reward. The reward

they finally get, though, is not exactly what they had in mind. Virtuous

Hungbu, of course, comes to the rescue, and Nolbu turns over a new leaf

— in his own way. |

| |

| The Money

Bug |

| Rich Miser

Ong doesn’t know it, but when he has the monk Hakdaesa thrown out

of his house he is asking for trouble. And sure enough, trouble arrives

for Ong the very next day in the form of a walking, talking, spitting image

of himself, conjured by Hakdaesa to teach Ong a lesson. Phony Ong persuades

everyone that he is the real Ong, and the real real Ong gets thrown out

of his own house. Finally, after several months’ wandering and begging

he repents; Hakdaesa decides he has learned his lesson and tells Ong to

go on back home. What is he going to find, though, when he gets there? |

| |

| Chun Hyang

Song |

| When Mong

Yong, the son of an aristocrat, falls into true love with Chun Hyang, the

daughter of a gisaeng, there is no way that trouble is not going to happen.

And it does. Chun Hyang’s mother allows the two lovers to marry. Too

soon, though, Mong Yong has to leave for Seoul to take the higher civil

service exam. He vows his undying love and loyalty. When the unprincipled

local magistrate Byon Satdo sets eyes on Chun Hyang, the term undying love

takes on special meaning: she has to choose between Mong Yong and life. |

| |

| |

| |